The Psoas and Quadratus Lumborum

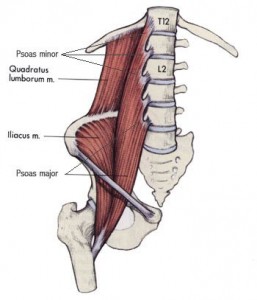

Regarding the psoas and quadratus lumborum, you can’t have problems in one without having trouble with the other.

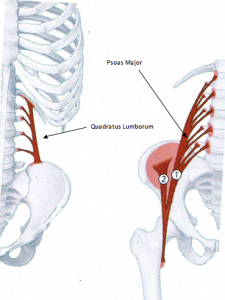

They are two muscles with completely different functions yet connect to the spine similarly, which leaves them inextricably related.

The quadratus lumborum, as its name implies, is a quadrate muscle which means that it acts as a stabilizer–in this case stabilizing the pelvis to the ribcage.

It functions mainly as a side-bending muscle.

The psoas is a hip flexor that also externally rotates the thigh. It also lifts the trunk off of the floor from a supine position.

In addition, the spine stacks vertically above the pelvis with the essential aid of the psoas, and it is also the most important muscle in a successful gait pattern.

Looking at the middle image above it is fairly easy to see–since they attach to almost the same places on the spine– why the tone in one of these two muscles so profoundly affects the other.

I’ll write another post about this soon but what goes for the psoas and quadratus lumborum goes for all of the muscles in what I’ll refer to as the pelvic belt.

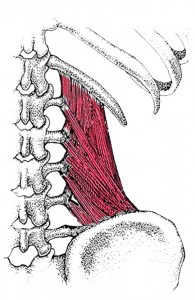

There will also be another post where I will add the diaphragm into the psoas and quadratus lumborum mix.

Using the tight psoas to start–the function of the psoas is to pull the lumbar vertebrae forward and down.

A tight psoas on either one or both sides pulls the lumbar further forward and down.

This tends to increase the curve of the lumbar spine, but it also changes the relationships of the muscles that attach there.

The quadratus lumborum is like a bed sheet pinned along three sides and spread out evenly.

When the psoas is tight the right side of the Ql can no longer expand as much as the left and you have a lopsided rectangle.

At that point you can hardly blame the quadratus lumborum for failing to function well.