Our bones hold us up, and our muscles move us. Our bones are connected by ligaments that are by nature very strong and taut. They don’t have much give and they shouldn’t change much in tone over the course of a lifetime (with exceptions of pregnancy and other hormonal situations). Muscles are very different. They only have tone if we exercise them to develop their strength and balance. Some people are born stronger than others but everyone needs to do the work to build muscle tone to support the alignment of our bones and allow for the chance of having good posture.

Supporting the Psoas Major: The Holy Trinity of Muscle Groups

I refer to three muscle groups as the holy trinity, working to support the ideal positioning of my favorite muscle, the psoas major. For the psoas major to be the wonder muscle that it is designed to be, it must be properly situated at its top and bottom, and it can’t find that placement by itself.

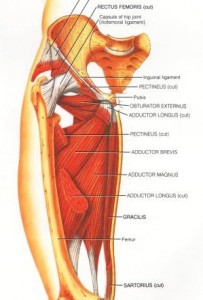

These three muscle groups are the adductors, muscles of the inner thigh; the levator ani, muscles of the pelvic floor; and the eight abdominal muscles.  There are five adductors muscles of the inner-thighs. They move the leg in toward the midline and help stabilize the pelvis. The shortest adductor is the pectineus, which attached high up on the inner thigh and into the pelvis. The longest, gracilis, attaches to the pelvis and all the way down to the shin. And the three middle muscles are adductor magnus, longus and brevis.

There are five adductors muscles of the inner-thighs. They move the leg in toward the midline and help stabilize the pelvis. The shortest adductor is the pectineus, which attached high up on the inner thigh and into the pelvis. The longest, gracilis, attaches to the pelvis and all the way down to the shin. And the three middle muscles are adductor magnus, longus and brevis.

All of these muscles attach around the pubic bone. But the adductor magnus, the biggest of them, attaches in two places— the pubic bone and one of your sit bones, the ischeal tuborosity. As a result of this second connection, the adductor magnus is responsible not just for moving your leg to the midline but also assists with internal rotation. And that ability to rotate the leg in is an absolute key to stabilizing and setting the psoas major.

The muscles of the pelvic floor are called the levator ani. Three muscles form a sling at the bottom of the pelvis that connects the tailbone to the pubis. This mass of muscle, about the thickness of your palm, is responsible for holding the pelvic organs in place and for control of rectal and urogenital function. Not only are these muscles bearing a lot of weight from above; they are also pierced by orifices that weaken the pelvic floor merely by their presence.

Continence is high on my list of priorities, and the pelvic floor and continence are dancing partners that we must train and respect. Because these muscles are involved with your eliminative functioning, they have more resting tone than any other muscle in the body and are almost always active—or you’d be peeing all night long. The pelvis and the muscles surrounding it serve a role unique to us bipedal mammals. Just like the psoas major, which is relatively dormant in quadrupeds but wakes up when standing upright brings it into positive tension across the rim of the pelvis, the pelvic floor has a much different role in the biped.

If you think of a dog or a cat or a horse, their pelvis is the back wall of the body rather than the floor. This leaves the organs in a dog to rest on the belly. In standing bipeds, the organs sit right on top of this muscle group, which frankly has enough to do without its newfound responsibility.

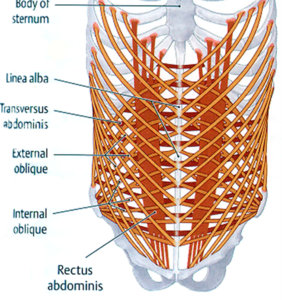

The final group of the holy trinity is the abdominal muscles, equally important for many different reasons. You have eight abdominal muscles—four pairs. All four sets of these muscles move in different directions though they are connected both through tendons and the fascia. The deepest of them is the transverse abdominis. It wraps from the back to the front, meeting at the linea alba a line of connective tissue that runs from the base of the rib cage to the pubic bone. We often refer to the transverse as one muscle, but it is two muscles that meet in the middle. This deep muscle when properly toned, provides a great deal of support for the lumbar spine.

The final group of the holy trinity is the abdominal muscles, equally important for many different reasons. You have eight abdominal muscles—four pairs. All four sets of these muscles move in different directions though they are connected both through tendons and the fascia. The deepest of them is the transverse abdominis. It wraps from the back to the front, meeting at the linea alba a line of connective tissue that runs from the base of the rib cage to the pubic bone. We often refer to the transverse as one muscle, but it is two muscles that meet in the middle. This deep muscle when properly toned, provides a great deal of support for the lumbar spine.

The next layer of abdominal muscles consists of the internal and external obliques, which are angled in opposite directions. These muscles help in twisting, rotating, bending and flexing the trunk and are also active when we exhale.

The third set of abdominal muscles is the rectus abdominis, the “six-pack.” This pair of muscles runs vertically, connecting at the pubis at its base and the sternum and three ribs at its top. An anatomical aside about the six-pack: The body has interesting and different ways of compensating for dilemmas of length and space. The length between the pelvis and the rib cage is really too big for one long muscle to provide support. As a result we have tendinous insertions that fall between what are actually ten small muscles. So we really build ten-packs, but we only see six of them. This pack is formed when we make these individual muscles big enough so that they essentially pop out from the tendons that surround them. Muscle is designed to stretch; tendons are not.

The physical and emotional health of the human body depends on the psoas major muscle that is well aligned and properly toned. This only happens if this holy trinity of muscle groups are aligned and toned as well.