The Weight Bearing Bones of the Forearm and Shin

The shin and the forearm each have two bones.

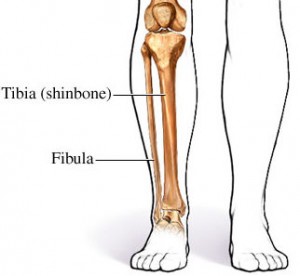

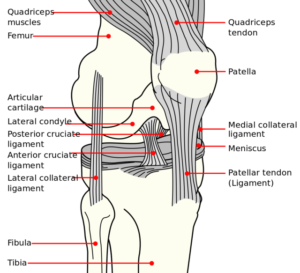

The two shin bones are the tibia and the fibula.

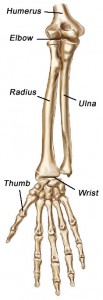

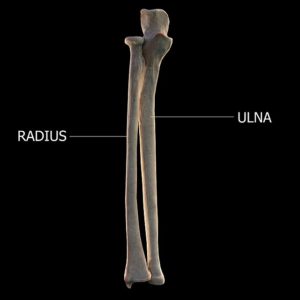

The forearm bones are the radius and the ulna.

The weight bearing bones of the forearm and shin are the radius and the tibia which are larger bones than their counterparts.

- The radius connects the inner hand and humerus.

- The tibia connects the inner foot and the femur.

Let’s look at downward facing dog in yoga as an example of a pose where we bear weight through both the hands and feet.

I’d say that a good percentage of students doing downward dog fail to align the weight bearing bones of the forearm and shin correctly.

In a downward facing dog I see most people let the weight in their hands and feet falls towards the outsides of the palm and foot.

When this happens you are dumping your energy into the smaller bones of the forearm and shin— the ulna and fibula— which aren’t designed to be weight bearing bones.

What this means is these bones can accept weight but cannot transfer that weight through other bones.

In the case of the fibula, it ends short of the knee and the ulna lacks the more literal connection that the radius has with the humerus.

When we stand, walk, do downward dog, and ground the extremities through the outer hands and feet, we deny the body the chance to function most efficiently.

Ideally, we gain access to the core by grounding correctly through the weight bearing bones of the hands and feet.

The opposite is true as well— we lose access to our core when we ground through the outsides of the hands and feet.

Weight Transfer

The bones hold you up, the muscles move you, and the nerves tell the muscles to move the bones.

This is a very simple yet effective way to look at how the body works.

The bones hold you up stacking one on top of the other so that weight can transfer from one to the other.

Unfortunately, poor posture, which affects all too many of us, messes with the ability to transfer weight successfully.

Poor posture takes a pretty common path.

Most people tend to have similar alignment issues.

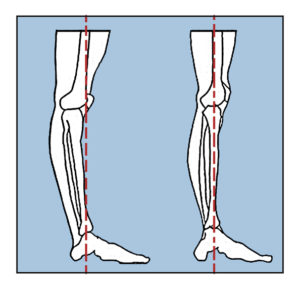

One common misalignment is hyperextension of the knee.

Hyperextension means taking a joint past its normal range of motion.

To compensate for knees that lock back, the thighs have to lean forward.

Not everyone hyperextends their knee but almost everyone leans their thighs forward.

Once the thighs are leaning forward the trunk has to lean back to compensate for the forward-leaning thighs.

And then the head has to go forward in an attempt to correct that.

.

.

Misaligned bones don’t stack successfully and when that happens weight transfer is interrupted.

This is a much bigger problem than it might seem.

A body that transfers weight well doesn’t expend nearly as much energy over the course of a day.

When the bones are misaligned the muscles have to get involved to help with weight transfer.

The problem with this is the muscles already have a job to do. They move us.

Muscles that have to help the bones hold us up don’t move us as efficiently.

Weight Bearing Bones: The Tiba & Fibula

Weight bearing bones stack on top of one another so that they can transfer weight up and down the line of bones.

In order to do that these bones need to have a connection to one another.

Looking at the picture above it is fairly easy to see the fibula is more connected to the tibia than the femur.

The tibia is a big fat bone that sits directly under the femur, or leg, at its top. At the bottom of the tibia, it connects to the talus bone.

The fibula, tibia, and talus make up the ankle.

The fibula is a skinny little bone on the outside of the shin. Its very bottom portion, along with the bottom of the tibia, encases the talus to create the ankle.

At its top, the fibula nestles under the outer edge of the tibia.

As a result, the weight that passes from the leg to the shin has little to do with the fibula.

This is important because we can associate the fibula with the outer foot and the tibia with the inner foot.

When we stand and walk, and do downward dog, we want more weight on the inner foot than the outer foot. But this isn’t usually the case.

You can check your shoes to see how they wear out.

If the wear is on the outer edge of your shoes you are using the fibula more than the tibia.

You want to push off with the big toe (inner foot) with each step.

This means the weight passes from the femur to the tibia to the talus and through the inner foot.

That is what we like to happen.

The Radius and the Ulna

The forearm is two bones, radius and ulna, between the humerus (arm) and wrist.

The radius and ulna have a slightly different setup than the tibia and fibula.

The ulna is the main bone of the forearm but the radius has slightly more weight bearing capacity that the fibula.

And there is a cool reason for this.

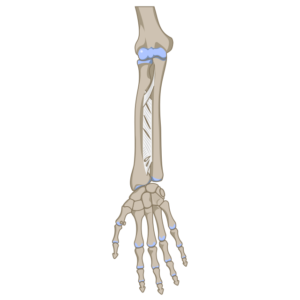

If you look at your shin and try to turn it in or out the bones remain in the same position lined up next to each other.

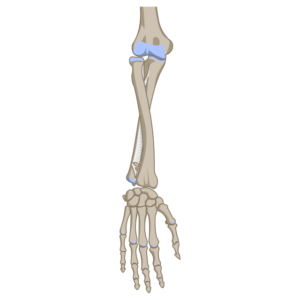

The radius and the ulna on the other hand can cross each other as shown in the images below.

But the ulna still has a much more concrete connection to the humerus, or arm, bone.

The radius forms a joint with the humerus but they are slightly separate.

The humerus and the ulna connect quite literally with the ball at the top of the ulna nestling into the base of the humerus.

The radius is on the thumb side of the forearm and the ulna is on the inside or pinky side.

Both the radius and ulna move together at their ends but only the radius moves with the wrist.

The ulna and radius move with the humerus with the help of the humerus.

The articulation of the ulna with the humerus forms the body’s truest hinge joint.

Both the shin and forearm bones have something called the interosseous membrane, connecting them together. This insanely strong connective tissue means they can’t move independently.

Back To Downward Dog

Making the best use of the body means using the weight bearing bones successfully.

Either right now, or the next time you do downward dog pay attention to how your hands and feet sit on the floor.

What I see most often is students allowing their energy to fall to both the outer foot and the outer hand.

It should be pretty easy to feel. You want the weight of both the hand and foot to be on the inside.

When you connect to both the inner hand and the inner foot you are starting to transfer weight successfully up and down the whole body.