Our poor calves.

The muscles at the back of the lower leg are either overlooked in relationship to their neighbors up north, the hamstrings, or doted upon for their size.

On the second point, I don’t understand why anyone would prize large calves but people do, and on the first point people should pay the same attention to stretching their calves that they do to stretching their hamstrings.

People tend to be tight in the back of the body—splayed open if you will. From top to bottom, the neck and lower back muscles along with the gluteus maximus, hamstrings, calves and achilles tendon are all tight in relationship to their opposite muscles at the front of the body.

People tend to be tight in the back of the body—splayed open if you will. From top to bottom, the neck and lower back muscles along with the gluteus maximus, hamstrings, calves and achilles tendon are all tight in relationship to their opposite muscles at the front of the body.

To develop an efficiently functioning body that ages well, these relationships have to change. The stretch at the left is a great way to start.

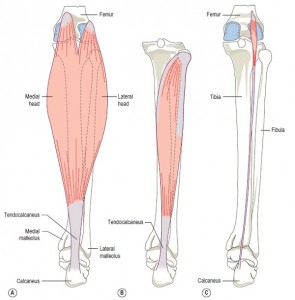

The anatomy of the calf muscle speaks mainly to two different muscles—the gastrocnemius and the soleus.

The bulge we see at the back of the lower leg is the gastrocnemius, the larger of the two muscles.

The gastrocnemius doesn’t actually attach to the bones of the shin— the tibia and the fibula—skipping them to connect to the femur bone and the calcaneus, or heel.

The gastrocnemius crosses paths with the hamstrings as it attaches on either side of the femur.

The gastrocnemius connects to the calcaneus via the achilles tendon along with the soleus which lies underneath the gastrocnemius attaching on both the tibia and the fibula.

The plantaris is a third muscle that attaches at the achilles tendon which is the largest tendon in the body and deserved of post of its own.

Looking the anatomy of the calf muscle we can see its importance in all forward movement through the soleus and gastrocnemius’ interactions with the foot and the leg.

Walking, running, and jumping are all facilitated by the calf muscles lifting the heel off of the ground.