Shoulders on the Back: From Plank Pose to the Floor

Trying to stand up straight often results in lifting the chest, pulling the arms back, and drawing the shoulder blades towards each other.

This is the pattern I see in almost everybody I work with when I ask them to stand up straight.

It is a terrible pattern yet one that is deeply ingrained in our culture.

If this is your pattern when standing, I can almost guarantee it will also be your pattern for exercise.

And for walking. And for most things.

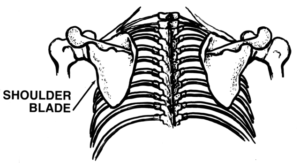

The shoulder is a structure made up of three bones.

- The arm, or humerus bone.

- The clavicle, or collar bone.

- The scapula, or shoulder blade.

The last two bones— the collar bone and shoulder blade, make up the shoulder girdle which hangs from the head and hovers above the rib cage.

What I want to talk about is the ideal position of the shoulder blades, in particular, when we exercise.

The shoulder blades are not connected to the ribcage and this gives the shoulder an incredibly wide range of motion to accommodate the use of the arms and hands.

Sometimes the arms are free and loose (talking with your hands, conducting an orchestra) and the shoulder needs to allow for that.

But we also need to lift, pull, and push things of varying weight and the shoulder needs to stabilize for that.

And if you hang from a bar with one hand, the entire weight of your body is hanging from that shoulder with much of the muscle work coming from the latissimus dorsi.

It’s awe-inspiring if you stop to think about it.

The shoulder is free and mobile but it also welcomes compression when we do planks and suspension when we hang.

The shoulder is free and mobile but it also welcomes compression when we do planks and suspension when we hang.

Things get even more fascinating, at least for me, if you consider the difference between the pelvis and the shoulder girdle.

Because we walk upright on two legs our pelvis needs to have minimal movement, so it has a bone— the sacrum— between the two hip bones to limit the movement of the legs.

In the shoulder girdle, there are muscles— the rhomboids— instead of a bone.

This is what allows for the shoulder blades to swing out to the side and up when we bring our arms over our heads, or towards each other if we clasp our hands behind our backs.

Unfortunately, the freedom of the shoulder also makes it uniquely susceptible to injury, and sometimes difficult to heal.

When it comes to exercise it doesn’t matter if we are targeting the abdominal muscles, the hamstrings & quadriceps, or the muscles surrounding the shoulder blade— we are trying to develop balanced muscle tone.

Balanced muscle tone in regards to the shoulder blades speaks to four muscles in particular.

- Pectoralis minor

- Lower trapezius

- Rhomboids

- Serratus anterior

Muscles always work in opposition to another muscle.

Here, the pectoralis minor & lower trapezius oppose each other, and the rhomboids and serratus anterior are opposites as well.

While the shoulder blades can wing out to the side— and draw toward each other— there is a neutral position they would like to be in when at rest.

We call that neutral position “shoulders on the back”.

This means well-aligned shoulder blades are equidistant from the spine and relatively parallel to each other.

When the shoulders are on the back successfully these four muscles are in balance exerting equal force to align the shoulder blade correctly.

Let’s look at lowering from a straight-armed plank position to the floor.

One of the reasons I love plank is that it is a mirror image of standing.

In plank, as in standing, the ears, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles should all form a straight line.

In plank, as in standing, the ears, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles should all form a straight line.

If this is the case, the four muscles above are all working to achieve this balanced alignment of the shoulder blade.

And then when the elbows bend and the body lowers down, nothing happens to the shoulder blade.

Does that make sense?

Ideally, the journey from plank to the floor happens without the shoulder blades moving because all four muscles did their job and stabilized the action.

Instead, rather than balance the shoulders on the back, one of two things usually happens when these muscles can’t balance each other out.

Of the four muscles above the only one that attaches to the front of the body is the pectoralis minor. It actually pulls the top of the shoulder blade forward and down.

This is fine if the lower trapezius can balance out the action to limit the ability of the pectoralis minor from pulling the shoulder blade too much.

Often the pectoralis minor is so much tighter than all three of these muscles and as a result, the head of the arm bone flies forward and down.

And that is not the way we want to lower from plank to the floor.

Is that what happens when you try this move? If you try this move?

If you don’t do plank to the floor it is a worthwhile aspiration and if you do, hopefully, you don’t collapse your arm bones the way I see so many people do.

It is my hope that we can create a muscular environment for the shoulder girdle that would keep the shoulder blades in the right place and allow for the arms to hang loose as designed.

When these four muscles are able to work as designed the shoulder blades will remain in its correct position and you can move the upper body with integrity.

This type of movement won’t be available without balanced muscular tone.