At the top of the body, the hyoid bone holds a place of the highest importance.

Deep in the core, the psoas reign supreme.

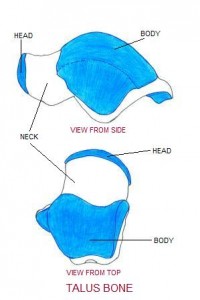

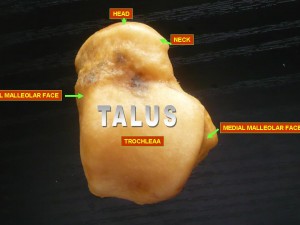

As we move down toward the feet we find the talus, a strangely shaped bone that connects the lower leg to the foot.

The movements of the ankle and foot as well as the transfer of weight from the legs to the feet are all dependent on the talus bone.

There are no muscles attached to the talus so its positioning and alignment depend on the bone surrounding it.

The talus which can be broken down into three parts—the body, neck, and head—is intimately involved in two essential joints of the lower body—the ankle joint (talocrural joint), and the subtalar joint (talocalcaneal joint and the talocalcaneonavicular joint).

The ankle joint is created by the meeting of the body of the talus, and the tibia and fibula— the two bones of the lower leg.

The Subtalar joint connects the head of the talus with the calcaneus or heel, and with the navicular bone, another of the tarsal bones of the hindfoot.

The ankle is a gliding joint facilitating the pointing and flexing (dorsiflexion and plantarflexion) of the ankle. The subtalar joint is responsible for the pronation and supination of the foot and its two distinct sections—where the talus meets the heel and where the talus meets the navicular bone, each influences different movements.

The talus has little access to our healing blood supply because it is almost completely covered by cartilage because it connects so many different bones.

The neck is the only part of the talus that is not surrounded by cartilage and receives blood as a result. Lack of a good blood supply is one reason why talus injuries can take a long time to heal.

***